‘In the whole British Empire there is no occupation in which a man may meet his end in so many ways as this one. The coal mine is the scene of a multitude of the most terrifying calamities…’ Friedrich Engels (1844)

My family worked in the Yorkshire coal mines for over a hundred years. Thankfully the long family tradition stretching back at least as far as the 1830’s ended with my father when he resigned from his colliery job in Barnsley as a young man. He was an assistant personnel manager and was therefore classified by the hardy Yorkshire miners as one of the bosses. During his first trip to the coal face, he emerged from the cage that had brought him down the main mine shaft. The miners reversed the ventilation fans as a practical joke causing the stagnant air and coal dust to blow straight into his face. For some reason the joke was lost on my father. He went on to have a stimulating and rewarding life above ground, away from the mines in a job that he loved!

I have nothing but admiration for coal miners past and present. Their labour powered the industrial revolution in Britain from around 1760 and they brought prosperity to the world. Their work was backbreaking, cramped, dangerous and dirty and for over two centuries they earned a pittance. They suffered from black lung (pneumoconiosis), silicosis, dust-related diffuse fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The back-breaking work often left them deformed. It frequently led to alcoholism, family breakdown and even in the twentieth century they would be extremely lucky to see out their sixtieth birthday.

Worst of all were the terrible accidents that too often befell the mine workers. Three incidents going back 150 years happened to members of my family and I relate their stories below.

In 1838, three of my relatives, from branches of my paternal grandmother’s side of the family, died in one of the most notorious mining disasters in British history. They were Elizabeth Carr aged 13, Francis Hoyland (also aged 13) and Samuel Atick (aged 10). They died with 23 other children, the youngest of which was Joseph Burkinshaw aged 7. The extract below comes from the UK Telegraph*.

“IT was a hot, sunny morning when the coal miners arrived at work at the Huskar Pit, Nabs Wood, near the village of Silkstone, South Yorkshire, England. But at 2pm on July 4, 1838, 180 years ago, a thunderstorm pelted the earth with rain and hailstones for two hours.

About 6cm of rain fell in a short time, filling up a stream in a nearby wood that was normally a dry creek bed. The stream, which had never been known to overflow, passed close by a “drift”, a shaft being used for ventilation. As the waters in the stream rose it threatened to inundate the shaft.

The rain had also put out the fire under a boiler for the steam engine powering the winch that pulled coal and workers to the surface. The miners were told to wait until the fire could be relit or to make their own way to the surface.

Most of the older men chose to wait at the bottom of the pit, but a group of about 40 boys and girls, also working in the mine, became impatient and decided to make their own way out via the small ventilation shaft. As they climbed upward, in pitch dark, the stream broke its banks and water poured down their escape route, washing 26 children back to a trap door that was shut, allowing water to build up. They either died from hitting the door or drowned.”

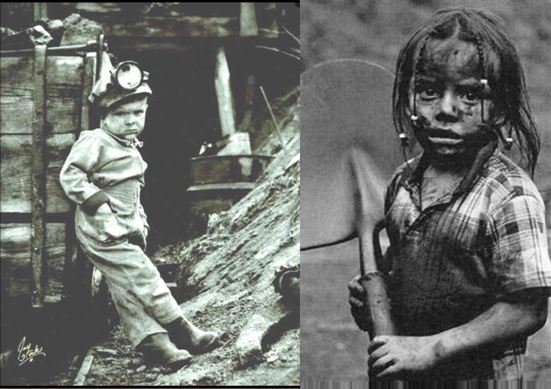

Miners were paid for each tonne of coal that they brought to the surface and children as young as five were employed in the mines to supplement their parent’s paltry wages who could not otherwise make ends meet. Seven-year-old Joseph Burkinshaw would have been a ‘trapper’. His job was to sit alone in the mine tunnels for up to twelve hours in the pitch black next to a ventilation trap door. When the older boys and girls passed by pulling a seven tonne corve of coal, Joseph’s job was to raise the trap door to let the corve through. **

A child worker harnessed to a corve, c1838

Elizabeth Carr, Francis Hoyland and Samuel Atick would have been ‘hurriers’. These young children were required to drag an empty corve down from the shaft bottom along passageways between 24 to 30 inches high and return with a full load from the coal face. One child would be harnessed to the front of the corve, while another would follow behind, pushing the load with their hands and their heads. Most hurriers would have large septic calluses on their legs, hands and knees and many were bald as a result of pushing corves up steep inclines with their heads. Their bodies were often ‘old’ and broken before they reached adulthood.

Elizabeth, Francis and Samuel, along with the other 23 children did not die in vain. The Huskar Pit disaster so appalled Victorian society that it led to the 1839 Royal Commission of Inquiry into Children’s Employment. The subsequent Mines and Collieries Act, 1842 resulted in a ban on boys younger than 10, and females of any age, working in coal mines and limited the hours of those who did work.

The worst coal mining disaster in England occurred in Barnsley on the 12th December 1866, although to my knowledge none of my relatives were among the victims. 361 miners and rescuers were killed when a series of explosions caused by firedamp ripped through the mine. The whole neighbourhood for three miles around shook as if an earthquake had occurred. The rescue effort took three days and many of the rescuers were killed by subsequent explosions in the mine.

Fourteen years later, on the 15th February 1880 in the village of Silkstone, near Barnsley my grandmother’s grandfather Edward Horne and his two teenage sons Janes and Herbert went to work at the nearby Cross Pit for the afternoon shift. As they were working, the roof collapsed, and they were buried under a mass of stone. It took five hours to pull their dead bodies from under the rubble.

Ten months later, on the 10th December 1880, my great, great grandfather Francis Hepworth aged 42, set off to work at the Hoyland Silkstone Colliery. He made several trips in the cage that took him from the surface to the coal face before he made his last fatal journey at 8:30pm. Half way down the 90-metre shaft, the wire rope attached to the cage snapped and the cage plummeted to the bottom. A new rope was attached to the cage and Francis Hepworth’s dead body was brought back up to the surface and taken to his widow Ann at their home in Barnsley.

As the world shifts away from coal to renewable energy, we must honour the memories of all the men, women and children who toiled in horrendous conditions and sometimes died in the coal mines over the last two centuries. It is not a job we should ever wish on our children, our friends or relatives. Times have changed and safety within the coal mines has improved immeasurably but it remains a dangerous and unpleasant occupation.

To those in society who still believe that a traditional job in the coal mines is preferable to a job in the new sunrise industries, I would say that the ghosts of thousands of miners killed in industrial accidents around the would accuse them of insincerity. It is time to move on and find a brighter, cleaner future for our children and leave the horrors of the past behind. There is no room for misplaced nostalgia when it comes to coal mining.

** https://www.stmuhistorymedia.org/child-labor-in-the-coal-mines/